I suspect it’s inevitable that at some point a student on my campus will be diagnosed with a highly communicable illness, be it the current coronavirus outbreak or another, perhaps even nastier, future disease. Given our responsibility to protect students and staff my expectation is that students with the disease would be individually quarantined and treated medically. But if the disease was discovered in, say, a dormitory or was prevalent in a community I can also imagine more drastic steps including a limitation on campus transportation and gatherings and possibly even the shuttering of classrooms. One can’t help but wonder how such a situation would affect the academic mission of the institution. If the threat prevailed for a long time would semesters be lost? How would that affect students’ ability to progress through their education? If classes are significantly disrupted will students get a refund on their tuition? There are potentially massive disruptions to the students, staff, and institution embodied in the realities of an epidemic of contagious disease.

My experience with the polar vortex may offer an insight into how a school might cope with such a scenario. On January 31, 2019, the Midwest United States was experienced a period of extremely cold temperatures and winds that drove the wind chill to temperatures near -30°F. In response my institution and many other academic institutions in the Midwest cancelled classes for two or more days (James, 2019; Slagter, 2019).

But I teach is an introductory STEM course entitled Extreme Weather. It seemed wrong to allow such a teachable moment to pass so I was determined to conduct class despite the classrooms being off limits. The challenge was amplified by the fact that I was traveling in Washington, D.C. and with the classroom shuttered the guest lecturer I had planned for the day I was away was not going to be able to help.

Fortunately, the class I teach is enabled by a technology that allows me to broadcast class synchronously so students who are ill or travelling (or lazy) can, nonetheless, interactively participate in class exercises and discussion during class time. The system (Echo360) includes a physical box in the classroom that takes the projected image and audio and both records it for future reflection and, optionally, broadcasts it to create a blended synchronous learning environment. Students can see what’s being projected, answer questions I may pose, ask questions that I or my teaching assistant will answer during or after class and indicate when they’re confused (I call that the “WTF” button) so I can see how many are confused as class is going on.

An extra feature of this system is called a “Universal Capture” option with which I, as instructor, can link to the box in the room from wherever I am and either record a video to shar with the class asynchronously or I can synchronously broadcast class to all students. Being on the road I did the latter and conducted a timely discussion about the “polar vortex” that was the root cause of the bitterly cold weather.

At the end of the semester, I conducted a survey with one of the questions being “Would you recommend live streaming be available in all your courses?” Of the respondents (N=196), 55% said “Yes, all courses” and another 32% said “Yes, but only all large courses.” Hence 87% indicated they would like this option expanded to at least all large courses at my institution.

Now I’m guessing that my instructional colleagues are going to recoil at the concept that their classes should be broadcast. They will argue, correctly, that the percent of students who opt to come to class will be significantly decreased with this option. In my course over the multiple semesters I’ve used this system the number so students who physically come to class has decreased to about 33% of the total by the end of the semester. But my attitude is that if a student can do well on my exams and homework without physically coming to class, why should I care? True, with fewer students the in-class discussions can be less fruitful and when I tell a joke the chances of getting a chuckle are diminished (though the odds were poor to start with). On the other hand, with the availability of the streaming option class “attendance” (measured by the number of questions student answer during class) averages over 85% every day.

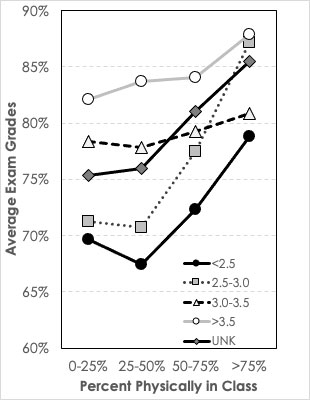

There is a downside to the remote delivery of class. Having extracted data from the Echo360 system about student behaviors (participation, number of questions asked, number of slides viewed, number of notes taken) the students who participate physically in the classroom more than 75% of days average 7% higher on exam grades than those who participate physically less than 50% of days (Samson, 2020). The data on behaviors also shows that students watch remotely take fewer notes, view fewer slides and participate in fewer classroom activities than those who attend physically more often. Also, students whose incoming grade point is less than 2.5 are far more likely to participate remotely than those with high incoming grade points. The data from the system though allows me to show the class evidence for why they might want to opt to come to class as it illustrates that even if they have not had academic success in the past the more they come to class the higher is their probability of getting a good score on exams.

What my experience with the polar vortex has taught me is that school can go on, regardless of what the world throws at us. Technology can allow us to continue with classes, including live interactive instruction. What is also teaches is that if we need to go to that model it behooves us to monitor how this mode of delivery will impact all students and that technologies to support remote synchronous learning must address strategies to encourage attentiveness and participation in the absence of physical attendance.

REFERENCES

Samson, P. J. (2020). Student Behaviors in a Synchronous Blended Course, Journal of Geoscience Education, in Press.