It is not unreasonable to imagine a day coming when colleges and universities will be faced with the decision of whether to allow classes and large gatherings of students to continue. Perhaps it will be as a result of the current coronavirus crisis or some future contagious pathogen. Dormitories could be under quarantine, classroom and other gatherings will be banned, students might even be asked to go home. I hope that day doesn’t come but it begs the question of what could we do if it does? Is it possible we can continue our mission using technologies to deliver courses synchronously or asynchronously and, if so, how will that change our course designs?

For instructors who teach face-to-face courses I’ve compiled some rules to consider should you ever need (or simply want) to switch to an online delivery model. These are lessons learned having offered a blended synchronous course for multiple years at the University of Michigan.

STEP 1: Acknowledge That There Have Always Been Students Who Couldn’t Get to Class

How did you deal with them? Ignore it? Tell them to get notes from a friend? Shame on you…

At a minimum be sure your class is recorded. I know it’s painful sometimes to see yourself faltering at the front of the room but empathize with your students. They get ill, they get drunk, they have to travel, let them review later. If you don’t allow recording because someone might steal your intellectual property, get over yourself. It’s hard enough to get students to reflect on your work and you worry others at your institution might steal your slides? Please.

STEP 2: This Could be a Good Time to Flip Out!

You have a couple of options for teaching online. You could record your session and have the students participate asynchronously or continue teaching at the prescribed days and times (to avoid conflict) synchronously (but record the session, see Point #1). However, it may be wiser to do both. That is, record a session but embed formative assessment questions into the video, then use occasional synchronous sessions to display their answers and provide feedback. The “flipped” classroom may be less popular with students as they have to do more work than sitting passively in class but has been shown (Bishop and Verleger, 2013) to be a more effective teaching method. Now’s a good time to try it.

STEP 3: Teaching Remote Students Requires Use of “Deliberate Engagement” Methods

Students participating in coursework remotely aren’t as engaged as students participating in person. There, I’ve said it. In this day of MOOCs and blended courses it’s not PC to throw shade on online learning but think back to the last time you participated in a webinar. You THOUGHT you could multitask and deal with e-mail while the session was streaming. Right? The reality is the immersive environment of a classroom may be boring but, even with the Internet, it doesn’t hold a stick to the distractions of a remote location. I swear the refrigerator knows how to signal me that I hadn’t eaten all the pickles yet.

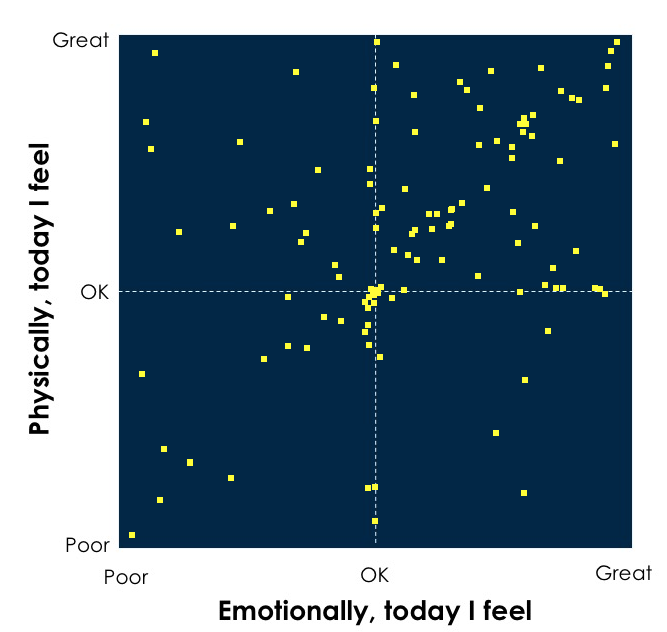

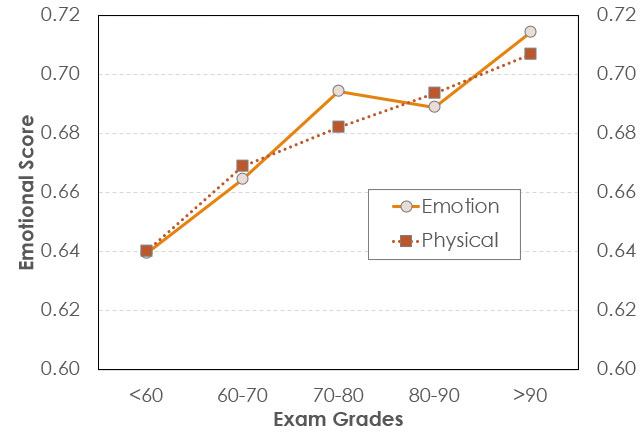

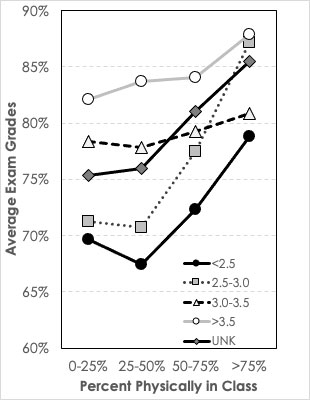

I’ve done research in my blended, synchronous course where students freely decide whether to come to class or watch from away. All students get points for participating in my formative assessment activities. Even with this incentive, the percent of questions answered by remote students is significantly lower than for students who come to the classroom. The system I use (Echo360) also tracks how many of my slides they view during class and, again, the remote students view far fewer slides than the student physically in class. Remote students tend to score 5-7 points less on course exams.

So if we must move to online teaching the walk-away message is we must find ways to make the online environment more immersive. I think the model of offering periodic formative assessment is key. I further would encourage you to link the students’ participation to a part of their grade. If our questions are valuable to their learning then we should reward participation. Beyond that think about ways to DEMAND participation. Use chat or other messaging methods and require their participation in class discussion.

STEP 4: Don’t Teach Like I Bowl

I doubt any of you have seen me bowl but it’s not pretty (or effective). Basically I wing the ball down the alley in the general direction of the pins and then pray. For a long time that was how I taught. Give the best lecture I could and pray that the students learned the concepts I was teaching. But like any good relationship, the key to success is good communication with an emphasis on good listening.

I’ve been spoiled by the system I use because it delivers a wealth of information about student behaviors. Did they log in during class time? How many activities did they participate in, How many “gradable” activities did they get right? How many slides that I projected did they view (they have to manually switch from slide to slide). With these data I can track student behaviors and have, over the years, been able to create statistical models about how behaviors are related to their exam scores.

The walk-away here is if you’re using a system that can track correctness then watch the results. Students who do well on the formative assessment tend to do well on exams. Those who do not, do not. “Listening” to students’ responses to assessments is a pretty strong first step in identifying students in trouble earlier in the semester.

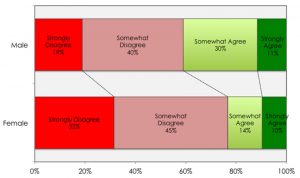

STEP 5: Listen for the Ones Who Aren’t Speaking

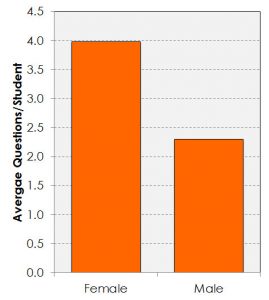

Some of my research has focused on the students who don’t speak up in class. In fact, in surveys of students I’ve found a dramatic difference in comfort with participating in verbal class discussion between women and men and 1st generation and other students. Many in class are uncomfortable speaking out. In an online environment maybe that will go away but it behooves us to track student questions and find methods that make the class discussions a less intimidating place.

The addition of an anonymous backchannel for students to pose questions digitally has led to a dramatic increase in student participation in class inquiry and those students who professed discomfort with participating in verbal inquiry were found to participate digitally at a level equal to or higher than others in the class. You are intimidating, give all students a less intimidating way to join the conversation.

References

Bishop, Jacob Lowell, and Matthew A. Verleger. “The flipped classroom: A survey of the research.” ASEE national conference proceedings, Atlanta, GA. Vol. 30. No. 9. 2013.